Nehushtan

from wikipedia.org

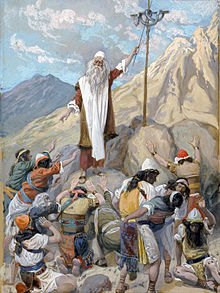

In the biblical Books of Kings (2 Kings 18:4; written c. 550 BC), the Nehushtan (Hebrew: Nehuštan) is the derogatory name given to the bronze serpent on a pole first described in the Book of Numbers which God told Moses to erect so that the Israelites who saw it would be protected from dying from the bites of the "fiery serpents", which God had sent to punish them for speaking against him and Moses (Numbers 21:4–9). In Kings, King Hezekiah institutes an iconoclastic reform that requires the destruction of "the brazen serpent that Moses had made; for unto those days the children of Israel did burn incense to it; and it was called Nehushtan". The term is a proper noun coming from either the word for "snake" or "brass", and thus means "The (Great) Serpent" or "The (Great) Brass".

Alternative translations

In the biblical Books of Kings (2 Kings 18:4; written c. 550 BC), the Nehushtan (Hebrew: Nehuštan) is the derogatory name given to the bronze serpent on a pole first described in the Book of Numbers which God told Moses to erect so that the Israelites who saw it would be protected from dying from the bites of the "fiery serpents", which God had sent to punish them for speaking against him and Moses (Numbers 21:4–9). In Kings, King Hezekiah institutes an iconoclastic reform that requires the destruction of "the brazen serpent that Moses had made; for unto those days the children of Israel did burn incense to it; and it was called Nehushtan". The term is a proper noun coming from either the word for "snake" or "brass", and thus means "The (Great) Serpent" or "The (Great) Brass".

Alternative translations

The English Standard Version of the Bible and the majority of contemporary English translations refer to the serpent as made of 'bronze', whereas the King James Version and a number of other versions state 'brass'. The Douai-Rheims 1899 edition has 'brazen'. Eugene H. Peterson, who created a loose paraphrase of the Bible as The Message (2002), opted for 'a snake of fiery copper'. The reference in 2 Kings 18:4 is translated as 'brasen' in the King James Version. Serpent image

Snake cults had been well established in Canaan in the Bronze Age: archaeologists have uncovered serpent cult objects in Bronze Age strata at several pre-Israelite cities in Canaan: two at Megiddo, one at Gezer, one in the Kodesh Hakodashim (Holy of Holies) of the Area H temple at Hazor, and two at Shechem.

According to Lowell K. Handy, the Nehushtan may have been the symbol of a minor god of snakebite-cure within the Temple.

In scripture

Snake cults had been well established in Canaan in the Bronze Age: archaeologists have uncovered serpent cult objects in Bronze Age strata at several pre-Israelite cities in Canaan: two at Megiddo, one at Gezer, one in the Kodesh Hakodashim (Holy of Holies) of the Area H temple at Hazor, and two at Shechem.

According to Lowell K. Handy, the Nehushtan may have been the symbol of a minor god of snakebite-cure within the Temple.

In scripture

Hebrew Bible

In the biblical story, following their Exodus from Egypt, the Israelites set out from Mount Hor, where Aaron was buried, to go to the Red Sea. However they had to detour around the land of Edom (Numbers 20:21, 25). Impatient, they complained against Yahweh and Moses (Num. 21:4–5), and in response God sent "fiery serpents" among them and many died. The people came to Moses to repent and asked him to ask God to take away the serpents. Moses prayed to God, who told Moses, 'Make thee a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole; and it shall come to pass, that every one that is bitten, when he seeth it, shall live.' (Numbers 21:4–9) This did not remove the source of the people's suffering; it enabled them to survive it.

The term also appears in 2 Kings 18:4 in a passage describing reforms made by King Hezekiah, in which he tore down altars, cut down symbols of Asherah, destroyed the Nehushtan, and according to many Bible translations, gave it that name.

Regarding the passage in 2 Kings 18:4, M. G. Easton noted that "the lapse of nearly one thousand years had invested the 'brazen serpent' with a mysterious sanctity; and in order to deliver the people from their infatuation, and impress them with the idea of its worthlessness, Hezekiah called it, in contempt, 'Nehushtan', a brazen thing, a mere piece of brass".

The tradition of naming it Nehushtan is not considered to be any older than the time of Hezekiah.

New Testament

In the biblical story, following their Exodus from Egypt, the Israelites set out from Mount Hor, where Aaron was buried, to go to the Red Sea. However they had to detour around the land of Edom (Numbers 20:21, 25). Impatient, they complained against Yahweh and Moses (Num. 21:4–5), and in response God sent "fiery serpents" among them and many died. The people came to Moses to repent and asked him to ask God to take away the serpents. Moses prayed to God, who told Moses, 'Make thee a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole; and it shall come to pass, that every one that is bitten, when he seeth it, shall live.' (Numbers 21:4–9) This did not remove the source of the people's suffering; it enabled them to survive it.

The term also appears in 2 Kings 18:4 in a passage describing reforms made by King Hezekiah, in which he tore down altars, cut down symbols of Asherah, destroyed the Nehushtan, and according to many Bible translations, gave it that name.

Regarding the passage in 2 Kings 18:4, M. G. Easton noted that "the lapse of nearly one thousand years had invested the 'brazen serpent' with a mysterious sanctity; and in order to deliver the people from their infatuation, and impress them with the idea of its worthlessness, Hezekiah called it, in contempt, 'Nehushtan', a brazen thing, a mere piece of brass".

The tradition of naming it Nehushtan is not considered to be any older than the time of Hezekiah.

New Testament

In the Gospel of John, Jesus discusses his destiny with a Jewish teacher named Nicodemus and makes a comparison between the raising up of the Son of Man and the act of the serpent being raised by Moses for the healing of the people. Jesus applied it as a foreshadowing of his own act of salvation through being lifted up on the cross, stating "And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: That whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life. For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life" (John 3:14–16).

Charles Spurgeon preached a famous sermon on "the Mysteries of the Brazen Serpent" and this passage from John's Gospel in 1857.

Book of Mormon

In the Book of Mormon, two prophets make reference to this event. The first is the prophet Nephi, son of Lehi in a general discourse, the second is many years later by the prophet Alma. Nephi tells the people that many of the Israelites perished because of the simplicity and faith required i.e., "and the labor which they had to perform was to look; and because of the simpleness of the way, or the easiness of it, there were many who perished." In the latter narrative, Alma tells the people of Antionum that many of the Israelites died because they lacked the faith to look at the brazen serpent. He then compared the brazen serpent to a type of Christ and exhorted the people to look to Christ and spiritually live.

Rabbinic literature

In the Gospel of John, Jesus discusses his destiny with a Jewish teacher named Nicodemus and makes a comparison between the raising up of the Son of Man and the act of the serpent being raised by Moses for the healing of the people. Jesus applied it as a foreshadowing of his own act of salvation through being lifted up on the cross, stating "And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: That whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life. For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life" (John 3:14–16).

Charles Spurgeon preached a famous sermon on "the Mysteries of the Brazen Serpent" and this passage from John's Gospel in 1857.

Book of Mormon

In the Book of Mormon, two prophets make reference to this event. The first is the prophet Nephi, son of Lehi in a general discourse, the second is many years later by the prophet Alma. Nephi tells the people that many of the Israelites perished because of the simplicity and faith required i.e., "and the labor which they had to perform was to look; and because of the simpleness of the way, or the easiness of it, there were many who perished." In the latter narrative, Alma tells the people of Antionum that many of the Israelites died because they lacked the faith to look at the brazen serpent. He then compared the brazen serpent to a type of Christ and exhorted the people to look to Christ and spiritually live.

Rabbinic literature

Inasmuch as the serpent in the Talmud stands for such evils as talebearing and defamation of character (Gen. iii. 4, 5), the Midrash finds in the plague of the fiery serpents a punishment for sins of the evil tongue (Num. xxi. 5). God said: "Let the serpent who was the first to offend by 'evil tongue' inflict punishment on those who were guilty of the same sin and did not profit by the serpent's example". One of the complaints in this case was dissatisfaction with the manna. Whereas the manna is believed to have had any taste desired by the person eating it, to the serpent all things had the taste of dust, in accordance with the words: "And dust shalt thou eat all the days of thy life" (Gen. iii. 14). It was very appropriate, therefore, that they who loathed the food which had given any taste desired, should be punished by means of that creature to which everything has the same taste (Midrash R. Num. xix. 22). The Mishnah does not take literally the words "Every one who was bitten by a serpent would look at the serpent and live," but interprets them symbolically. The people should look up to the God of heaven, for it is not the serpent that either brings to life or puts to death, but it is God (Mishnah R. H. 3:8, B. Talmud R.H. 29a). In the course of time, however, the people lost sight of the symbolical meaning and regarded the serpent itself as the seat of the healing power, and they made it an object of worship, so that Hezekiah found it necessary to destroy it (II Kings xviii. 4). The question that puzzled Heinrich Ewald ("Gesch. des Volkes Israel," iii. 669, note 5) and others, "Where was the brazen serpent till the time of Hezekiah?" occupied the Talmudists also. They answered it in a very simple way: Asa and Joshaphat, when clearing away the idols, purposely left the brazen serpent behind, in order that Hezekiah might also be able to do a praiseworthy deed in breaking it. In art

_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall'Orto_25-Apr-2007.jpg) There is a Brazen Serpent Monument on Mount Nebo in Jordan created by Italian artist Giovanni Fantoni. Similarly, on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo painted a mural of the Israelites' deliverance from the plague of serpents by the creation of the bronze serpent.

There is a Brazen Serpent Monument on Mount Nebo in Jordan created by Italian artist Giovanni Fantoni. Similarly, on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo painted a mural of the Israelites' deliverance from the plague of serpents by the creation of the bronze serpent.